Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

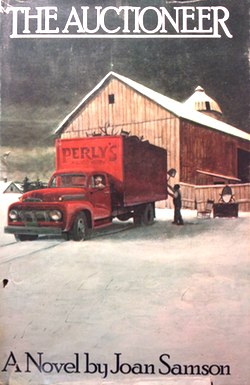

A brief bestseller when it debuted in 1975, Joan Samson’s The Auctioneer has been totally forgotten. Sites like Will Errickson’s Too Much Horror Fiction have kept its tiny flame from becoming completely extinguished, but it’s basically a literary shooting star that flared once, and was gone. Contributing to its short shelf-life, Samson wrote The Auctioneer in her 30s and died of cancer shortly after it was published. Her death is our loss. This is one of those books you stumble across with no expectations, and when you finished reading you think, “Why isn’t this more famous?” Spare, unforgiving, and hard all the way down the line, if Cormac McCarthy had written Needful Things, you’d get The Auctioneer.

Harlowe, New Hampshire is a hardscrabble Yankee farming community where change comes slowly. The center of town is a quaint slice of Americana that attracts city people driving up to see the leaves change but out on the farms indoor plumbing and telephones are still a novelty. John Moore and his wife, Mim, work one of these farms, scratching out a living, their real estate far more valuable than any crop they can possibly produce, but they hang on because they live in “…a house that had been lived in for generations by the same family.” Things are continuing pretty much as they always have when Bob Gore, the chief of police (and the only member of the police force), drives out to ask for any old junk they have lying around for a police benefit auction. The whole country is going to hell so some of that urban blight is bound to make its way to Harlowe eventually. In fact, there was a hold-up and a robbery recently, so Gore figures he’d best have a couple of deputies on hand, just in case.

The Moores give him some old wagon wheels, and the following week Gore comes back saying that if one auction was good, “Two’s better.” Besides, any day now all that “traffic and filth” is going to start coming to their fine city. And there’s a peach of an auctioneer helping him out, one Perly Dunsmore, who recently moved into the Fawkes mansion on the town square after the tragic strangling of Miss Fawkes. “Perly ain’t ordinary,” Bob enthuses. “Fact, there’s a man could do any damn thing he set his mind to…Perly knows about land, and there’s big things brewin’ in Harlowe to do with land.” The Moores figure they can spare an old buffet, and off it goes.

The wedge is in, and now it begins to split the wood. Every Thursday, Gore shows up requesting more items “for the auction.” When the donations start to hurt, he sends his brand new, highly armed deputies for the pick-up, and eventually the house is stripped of everything but some old mattresses the Moores sleep on. Then the deputies take the mattresses. When John protests, the deputies gossip about all the accidents befalling citizens recently. Fires, car accidents, the kind of things that would leave a young wife a widow and her little girl an orphan. Besides, they didn’t kick earlier over the wagon wheels. What’s the problem now? These auctions are for a good cause.

Like Count Dracula, Samson keeps Perly Dunsmoore offstage for most of the book, but when John finally confronts him, Dunsmoore turns out to be more than his match, talking circles around the farmer. In fact, he’s so convincing that he’s taken to auctioning off some of the town’s children. After all, they don’t want to disappoint the summer people who are now flocking to Harlowe for the auctions. That would be a real blow to the economy. Pushing, persuading, threatening, and constantly using the threat of a phantom recession, Dunsmoore turns this quiet little town into a living hell and one by one people start to crack under the pressure.

It all sounds far too metaphorical for its own good, but Samson plays it straight, and she doesn’t waste any time getting to the action. By page two things are driving forward relentlessly, and by the halfway mark John Moore has gone underground to become an angel of vengeance, convinced that the only way to liberate Harlowe is to destroy it. By the end of the book, as a lynch mob rages out of control, all semblance of the sleepy rhythms that washed through the first quarter of the book are long gone, never to return. The auctioneer has poisoned this town and left nothing behind but toxic waste. The horror comes from the convincing case Samson makes that with the slightest application of the right kind of pressure we’re only too ready to smash the things that we know can never be mended.

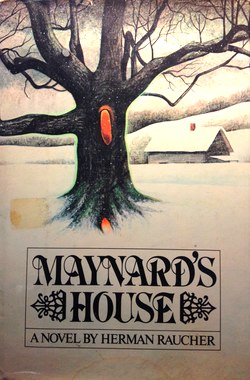

The Auctioneer is a rejoinder to the back-to-the-country fad that America experienced from the late Sixties through the early Eighties as city slickers moved to communes and small country towns looking for a simpler way of life. Thomas Tryon skewered that instinct hard in Harvest Home (1973) and Samson’s The Auctioneer skewers it from the other direction, putting the focus on the residents whose farms are bought up at prices they can’t refuse, then chopped into subdivisions and destroyed. Herman Raucher, author of Summer of ‘42, played another riff on this theme with Maynard’s House (1980) his (literally) haunting novel about a Vietnam vet who retreats to rural Maine to get his head together, only to wind up the victim of an undead witch.

The Auctioneer is a rejoinder to the back-to-the-country fad that America experienced from the late Sixties through the early Eighties as city slickers moved to communes and small country towns looking for a simpler way of life. Thomas Tryon skewered that instinct hard in Harvest Home (1973) and Samson’s The Auctioneer skewers it from the other direction, putting the focus on the residents whose farms are bought up at prices they can’t refuse, then chopped into subdivisions and destroyed. Herman Raucher, author of Summer of ‘42, played another riff on this theme with Maynard’s House (1980) his (literally) haunting novel about a Vietnam vet who retreats to rural Maine to get his head together, only to wind up the victim of an undead witch.

Totally forgotten today, even more so than Samson’s Auctioneer (which has at least been reissued by Centipede Press), Maynard’s House manages to wring maximum terror out of the admittedly silly scenario of a man being chased by a pointy witch’s hat. Austin Fletcher is a pissed-off vet who heads up to Maine to take possession of a tiny house in the wilderness willed to him by Maynard Whittier, his buddy who died in combat. The house lies just outside the tiny town of Belden, and after nearly freezing to death in a snowstorm, Austin arrives to discover that it’s a perfect slice of snowy heaven, like a Thomas Kincaid painting.

After taking possession, Austin learns that the house belonged to a witch who was hung 350 years ago, and her spirit might still be hanging around the place. Between the haunting, the actual dangers of nature (like a very, large, very pissed off bear), the locals who don’t quite take to him, and his own post-traumatic stress syndrome, it’s not long before Austin is battling for his life. Whether the end of the book is a hallucination or an actual, full-on attack by the supernatural, it doesn’t matter. By the time Austin encounters the corpse of the witch, “dangling and twitching, spitting urine and drooling feces, laughing hoarsely at her own never-ending agony” things are horrifying enough. Literally or metaphorically, there’s no escape.

The Auctioneer and Maynard’s House are the kind of books you stumble over by accident and love all the more for their obscurity. They’re sharp, idiosyncratic, and aggressive rebukes to the idea that life is somehow better out in the country, and like the houses that lie at the heart of each book, they are crafted with care, and built to last.

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his story, “Mofongo Knows” appears in the anthology, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination.